Measuring combined home and vehicle energy burdens reveals significant disparities by income, race, and ethnicity. These combined burdens provide a more holistic picture of household energy affordability and can help inform efficiency policy.

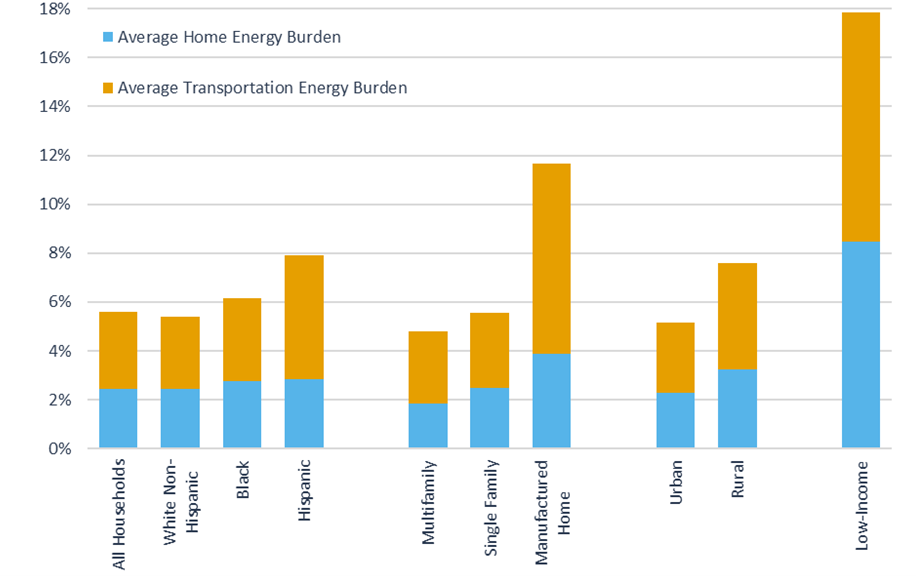

New research from ACEEE shows that combined home energy and transportation fuel costs make up a substantial share of household income. On average, low-income households spend 17.8% of their income on energy bills and transportation fuel, more than three times the national average. A staggering three in four low-income households experience high combined energy burdens, which we define as spending more than 12% of their income on energy.

Combined energy burdens also vary based on race and ethnicity. Hispanic households experience the highest combined burdens, spending on average 7.9% of their income on combined energy costs, 42% above the national average burden. Black households experience the second-highest combined burdens, spending on average 6% of their income on combined energy costs, roughly 10% above the national average.

Though differences in income account for much of the disparities in combined energy burdens, more burdened households may experience high energy costs due to myriad intersecting factors. Low-income residents may own or rent homes built to out-of-date energy codes or in need of significant weatherization or appliance upgrades. Rural or suburban residents may live far from their jobs and essential services, or otherwise rely on personal vehicles for long commutes. For example, the average transportation energy burden of Hispanic households is relatively high partly because many of these households live in the South or Southwest, which have lower population densities and limited public transportation options compared to other areas, and these households are more likely to work in rural areas with long commutes.

The figure below breaks down the combined energy burdens of various household types.

Building type, distance from city centers, and access to public transportation—often products of zoning policies—are all contributing factors to a household’s overall energy burden.

The need for comprehensive energy burden measurements

Existing energy burden research typically looks at home or transportation energy spending—namely utility bills or gasoline costs—in isolation. Some research has attempted to estimate combined energy burdens by combining data from two asynchronous and infrequent datasets. Our combined estimates are the first to compare home energy and transportation energy costs using the same dataset, the Bureau of Labor Statistics’ Consumer Expenditure Survey, a detailed household survey released twice a year.

Broadly, housing and transportation costs (rent, mortgage payments, car loan or lease payments, and operating costs) make up the first and second largest household expenditures. Energy costs make up just one portion of these categories but can vary substantially due to factors outside of residents’ control, such as weather, market forces, the efficiency standard to which a home or car is built, and proximity to transit, employment centers, and essential services. Households with the highest energy burdens often have difficulty investing in better home or transportation efficiency or proximity to transit, highlighting the need for efficiency programs to increase access. For example, some residents can only afford homes in less expensive areas far from city centers or their work, requiring more driving time and increasing their transportation costs despite their income constraints.

Some efficiency policies may affect the relationship between the two types of energy burdens. For instance, switching to an electric vehicle that is charged at home will increase home electricity bills, but the savings in gasoline costs will likely more than offset the electric bill increase, demonstrating why housing energy burdens should not be considered separately from transportation energy burdens.

These energy costs are not experienced in isolation, so household efficiency metrics and policies should not be considered in isolation. A more holistic metric will be essential to tracking overall energy affordability for U.S. households and can inform well-rounded efficiency policies.

Efficiency policy should consider energy burdens from homes and transportation in tandem

Policies designed to address energy affordability—such as bill assistance, weatherization, or efficient vehicle incentives—should be crafted with a special focus on groups that are disproportionately impacted by energy costs.

Home energy burdens serve as an important metric in shaping home efficiency policy. For instance, the Weatherization Assistance Program (WAP), the Low-Income Heat Assistance Program (LIHEAP), and numerous state and utility weatherization and bill support programs all rely on home energy burdens either to evaluate the success of their program or inform program design. Though less embedded in existing policy to address energy affordability, research on transportation energy burdens has highlighted the importance of vehicle efficiency and access to essential services and transportation in improving affordability and reducing emissions.

Moving forward, measuring combined burdens can ensure a fuller picture and inform better energy efficiency policies. For example, as some households begin to electrify their vehicles, utility programs could consider designing programs to incentivize more-efficient electric vehicles to minimize electricity consumption. States or local governments could consider energy assistance programs that address low-income or rural households’ transportation costs by expanding access to public transportation and programs to support the transition to more-efficient vehicles.

Further research on combined energy burdens can support policymakers in designing policies that address the full impact of home and transportation energy costs on families.