Washington, DC—Electric heat pumps generally offer the cheapest way to cleanly heat and cool single-family homes in all but the coldest parts of the United States in coming decades, according to research released today by the American Council for an Energy-Efficient Economy (ACEEE). In very cold places, the analysis finds, electric heat pumps with an alternative fuel backup for frigid periods minimize costs.

Register now for the report webinar today, July 27, at 12:30pm ET

As states and utilities look to reduce planet-warming emissions, they need to help households transition to cost-effective heating and cooling that use clean energy. To look at options, the ACEEE report evaluated the energy use of several thousand homes across the United States. It considered life-cycle costs for equipment and energy under a scenario in which the electric grid and heating fuels are largely decarbonized beginning in 2030.

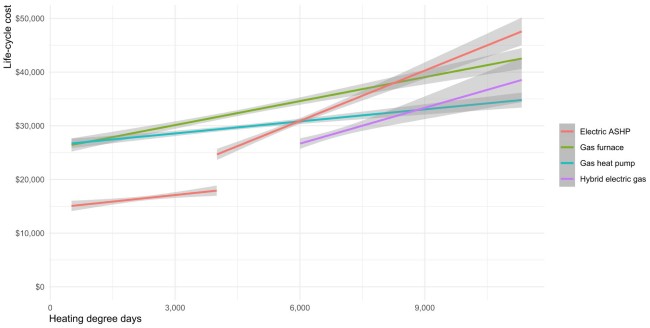

For homes with up to four units, electric heat pumps generally minimize heating and cooling costs in places that are warmer than Detroit. These places have fewer than 6,000 heating degree days (HDD)—a measure of how much seasonal temperatures fall below 65°F. In colder climates, electric heat pumps combined with use of a backup fuel during frigid periods (below 5°F) generally minimize these costs. For water heating, electric heat pumps minimize costs in all climates.

“Our findings are good news for consumers and for the climate. Electric heat pumps, which heat and cool, are the cheapest clean heating option for many houses, especially now that we have cold-climate models,” says Steven Nadel, report coauthor and ACEEE’s executive director. “We need to accelerate the use of electric heat pumps, emphasizing cold-climate models in places colder than Maryland,” he adds, noting Maryland has about 4,000 HDD.

Electric heat pumps are energy efficient because they don’t create heat by burning fuels but rather move it (during the heating season) from cold outdoors to warm indoors. Cold-climate models, an advance in technology, operate efficiently at temperatures as low as 5°F. Their energy costs, however, are minimized if an alternative fuel backup kicks in when it gets colder than 5°F for long periods.

For large multifamily buildings, electrification is more complex. Individual units generally don’t use a lot of energy, so recouping the costs of electrification takes longer. Based on limited and preliminary data, the analysis finds that using alternative fuels in condensing boilers often minimize life-cycle costs, whereas using electric heat pumps in apartments now with furnaces generally lowers costs.

The report recommends incentives or other assistance for low- and moderate-income households, whose homes are often the most difficult to decarbonize. Notably, it calls for help to reduce the costs of ductless electric mini-split heat pumps in multifamily buildings. The analysis finds that higher-income households are more likely to minimize costs with electric heat pumps, because they have newer—and more likely, single-family—homes with air-conditioning and improved energy efficiency.

“Electrification will play a crucial role in decarbonizing homes, but the transition will happen slowly as long as inexpensive fossil fuels are widely available,” says Lyla Fadali, report coauthor and ACEEE senior researcher. To accelerate this transition, the report also calls for research and development of heat pumps, minimum efficiency standards for heating equipment, restructuring electric (and perhaps gas) rates, and a price on carbon.

The report sees a role for energy efficiency in this transition as well, finding it often reduces life-cycle costs. For many homes, a moderately sized package of efficiency improvements has the lowest life-cycle costs. For homes in cold climates with oil or propane heating, or above-average energy bills, a deep retrofit often reduces these costs.

The report models the potential life-cycle costs of decarbonized heating options based on the energy use of about 3,000 homes heated with fossil fuels that are part of the Department of Energy’s 2015 Residential Energy Consumption Survey. It assumes the use of cold-climate pumps in places with 4,000-plus HDD. It estimates the costs of using decarbonized energy for heating options beginning in 2030, estimating that the costs for gas more than triple and costs for electricity increase 30% in Minnesota. Its results, based on medium cost assumptions for equipment and energy, change modestly at higher and lower energy prices and system costs.

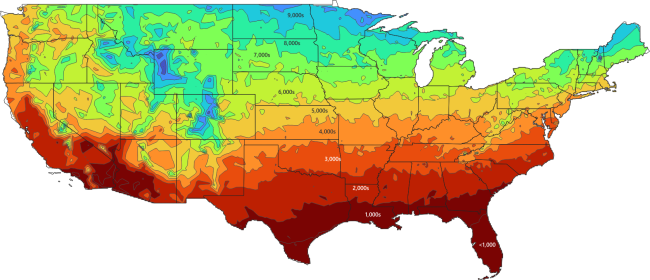

This 2015 survey uses old climate data. It looks at the average HDD for each home based on 30-year (1981–2010) averages. Because of climate change, most of the United States is warming, and its HDD are declining. To provide a more up-to-date picture, ACEEE used U.S. government data to calculate 15-year (2006–20) averages, as shown in the map below. Philadelphia averages about 4,300 HDD, while northern Minnesota often has more than 8,000.

As the United States continues to warm, fewer places will have more than 6,000 HDD—the inflection point beyond which electric heat pumps may need decarbonized fuel backup to operate most cost-effectively. Instead, cooling needs will increase. Electric heat pumps can efficiently meet these needs in all climates.

Average heating degree days (HDD) in the United States based on averages over the 2006–20 period. Lines between colors are approximate. Source: map created by ACEEE based on data from the National Centers for Environmental Information, 2021.