As another round of global climate talks has concluded, many observers wonder whether the 2016 election means the end of greenhouse gas regulation in the United States. More specifically, what happens to the Clean Power Plan?

Even before the election, the Clean Power Plan was already years away from being finalized. Implementation of the rule is currently stayed as it moves through the courts. Even if it sails through the courts unscathed and the original compliance schedule remains in effect, states would not have to meet their first targets for curbing power plant emissions until two years after the next presidential election (2022).

When it comes to environmental regulation, it’s best to take the long view. Rulemakings made pursuant to authority under the Clean Air Act are generally litigated and take years to develop. They often span across multiple administrations. Take the Cross-State Air Pollution Rule, the Environmental Protection Agency program to limit emissions of nitrogen oxide and sulfur dioxide. It took decades to evolve. There were multiple years when the EPA didn’t act or the rulemaking just sat in courts.

If the question is: Will we implement a final rule called the CPP? Probably not, but the Supreme Court and the Clean Air Act require the EPA to regulate greenhouse gases from existing power plants. How a Donald Trump administration might navigate this issue is an open question with multiple potential paths. Here at ACEEE, the Clean Power Plan has been a major area of focus, but not for the reasons you might think.

The Clean Power Plan never contained any requirements for energy efficiency. Yet it shined a spotlight on energy efficiency and its effectiveness in reducing greenhouse gas emissions. It was a very visible effort that got people thinking about energy efficiency because of its health and environmental benefits. It sparked conversations between utility regulators and air regulators in states—some of whom had never considered the emissions reductions they had been achieving through existing energy efficiency programs. I feel fairly confident in saying that either the prominent role of energy efficiency in reducing greenhouse gas emissions wasn’t well understood, or the policy mechanisms and tools for implementing such efficiency weren’t well understood.

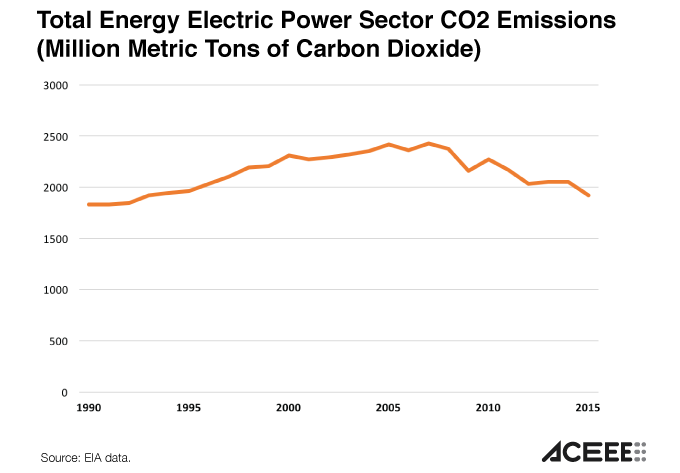

The work that needs to be done has never been about a single rulemaking. All of the health and environmental benefits that come with energy efficiency are still possible, with or without the Clean Power Plan. Energy efficiency has always been here, and it will remain vital for our health, economy, and infrastructure resiliency. Furthermore, states will continue to bear the primary responsibility for protecting public health. The Clean Power Plan was designed to reflect a direction in which the states were already heading. Data from the Energy Information Administration shows that even without the rulemaking, greenhouse gas reductions from the power sector have been steadily declining. States are already reducing greenhouse gases and using energy efficiency to create jobs, improve housing, and protect the safety and security of low-income and fixed-income families.

We’ll see what happens with the Clean Power Plan, but in the meantime, we can move ahead with good policies that can be implemented with ‘no regrets’ during this period of regulatory uncertainty. States and cities can create jobs, reduce energy costs, and position themselves for a competitive advantage with energy efficiency. Whether you’re Republican or Democrat, wealthy or financially struggling, saving energy is a good idea.