Millions of people work to save energy in the United States.

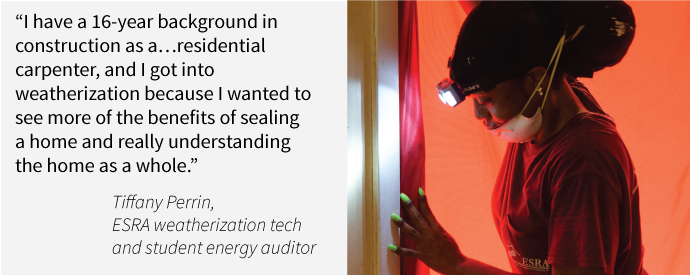

In our new multimedia project, People Who Save Energy, we introduce you to the people in this diverse and growing workforce. They work in every state, across industries and technologies. They make, sell, and install efficient products such as ENERGY STAR® appliances, build well-insulated homes, or offer energy-saving services such as weatherization. They are passionate about saving energy.

Fact Sheet: Energy Efficiency—Jobs and Investment

Fact Sheet: People Who Save Energy: Efficiency Workers

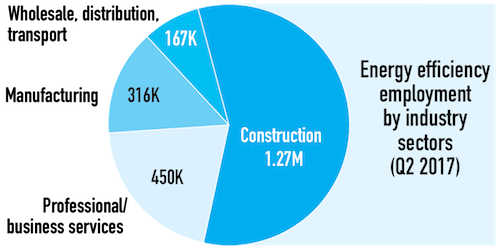

At least 2.2 million people work some or all of their time on energy-efficient technologies and services, according to a 2017 report for the US Department of Energy. They outnumber the 1.9 million who work to produce electricity (solar, wind, nuclear), coal, oil, and gas. More than half of these jobs occur in construction. In fact, one of every five US construction jobs now deals with products proven to save energy.

Other jobs are related to energy efficiency, too. The DOE reports another 0.7 million jobs that focus on vehicle fuel economy and alternative fuel vehicles and three million jobs that sell efficient (and other) appliances and building materials. These numbers don’t include the indirect jobs that result when customers spend or invest the money they save in lower energy bills somewhere else in the economy.

Energy efficiency not only supports millions of US jobs, but attracts billions of dollars in capital each year. It is probably the single most important source of energy we have. The economy has grown by almost 150% since 1980. Powering that growth has been an increase in energy consumption of about 20 quadrillion BTUs. Over that same period, energy efficiency delivered more than 50 quads worth of energy services, far outpacing not just oil but also coal, gas, nuclear power, and all other sources of energy combined. (See our report The Greatest Energy Story You Haven't Heard.)

At the same time, while efficiency employment grabs far fewer headlines than automotive jobs, a recent report by the Department of Energy found that efficiency employs about twice as many people.

Yet people generally don’t think about energy efficiency in the same way they think about other sources of energy or other sectors of the economy. That’s understandable, because energy efficiency is not a commodity like oil, whose price we follow closely, and it’s not a bellwether industry like the auto sector, whose production and employment are key economic indicators. Energy efficiency itself is largely invisible, and its economic impacts are spread throughout the economy, making them hard to see.

Investing in energy efficiency is vital. A key driver of long-term economic growth is productivity: how much we can create with the resources we have at our disposal. At its simplest, energy efficiency is productivity: getting more out the energy we use. Investments in energy efficiency feed the engine of long-term economic growth and the jobs that result from it.

We see the power of this productivity when we do economic modeling of efficiency investments. We use the ACEEE DEEPER model to assess the economic implications of a range of efficiency policies and investments. In talking about the job-creating power of efficiency, most people imagine workers in hard hats installing efficient windows and other equipment. These are important and easy to identify, but our modeling consistently shows that for every job installing energy efficiency measures, the energy these measures save creates between one and three more.

Investments in energy efficiency not only create jobs on their own but they also free up resources to invest and create jobs elsewhere in the economy. This is the power of energy efficiency. It helps us do more with less, creating a faster growing, more stable economy and the dynamic job growth that comes with it.

Case Study

When Elena Chrimat could not get a buildings job in the recession of 2008 in Arizona, she cofounded a small business, working out of her 1989 Land Cruiser to save energy in homes. Ideal Energy LLC now employs 10 people in Tempe. They did 1,179 jobs last year, including energy audits, installing efficient air conditioners and insulation, and sealing air leaks. With efficiency she “didn’t just want a job to make a buck [but] to do something more impactful.” See more stories like this in the fact sheet "Energy Efficiency—Jobs and Investment."

More than 500 people work at the Johnson Controls plant in Toledo, Ohio, making advanced batteries that can be used with Start-Stop technology in cars and trucks such as the Ford F-150 and Chevy Malibu. Start-stop turns off the engine when you step on the brakes at a signal or in a traffic jam but keeps the air conditioning and electronics running. It reduces gasoline use in the car by about 5%.

Tom Hughes, 31, worked in the auto industry for a decade, repairing cars and helping run dealerships. He didn’t find the work gratifying so a little more than two years ago, he switched careers. Following somewhat in the footsteps of his dad, a building inspector, he learned how to inspect homes for energy efficiency. He joined PEG, a Virginia-based engineering and consulting firm, as a HERS (Home Energy Rating System) rater. “I didn’t want to do a desk job,” he says. He enjoys doing blower door and duct testing in the field, and if a home doesn’t meet code or Energy Star standards, figuring out why. “It’s the best job I’ve ever had,” he says, adding people appreciate when you help them save money on their utility bills. Recently promoted, Hughes is now training others in the field.

Rich Podrez (far left), a back tender at Flambeau River Papers, works to secure a large roll of paper before moving it to the shipping or converting facility. Image by Mike De Sisti. USA, 2012.

In 2006, the paper mill that was the heart of the economy in Park Falls, Wisconsin, shut down. But new owners led by Butch Johnson bought the mill, rehired about 300 employees, and invested in energy efficiency improvements including in the steam system, pumps, lighting, heat recovery, and process improvements. More than $10 million in savings in the first few years made the plant more competitive. Johnson said that without state assistance on energy efficiency, “our mill would be less competitive, less green and less energy efficient, and we may not be in business today.”

Jobs Legislation

Energy efficiency naturally fits in the discussion of crafting legislation to create jobs. Energy efficiency projects are labor intensive and lower energy costs for consumers and businesses, allowing them to spend on more productive investments. Particularly in the badly-hit construction sector, energy efficiency projects can put people back to work in the energy services sector conducting energy audits and retrofits. The intersection of jobs and energy efficiency goals support a growing movement for economic growth in an environmentally sustainable manner. Training a clean energy workforce will be imperative to compete in a carbon-constrained economy.

The first major piece of jobs legislation that incorporated energy efficiency was the American Recovery and Reinvestment Act (ARRA), which supported numerous energy efficiency initiatives including home weatherization. The energy-related ARRA funds will allow cash-strapped businesses and state governments to lower utility bills. Schools, hospitals, and other public facilities will also use ARRA-funds to lower operating costs and invest energy savings into important services for communities. The energy programs funded by ARRA will leverage substantial private sector investment, spurring job creation in industries hit hard by the recession such as construction and manufacturing.

Home and building retrofits continue to garner support for inclusion in potential job-creation bills as the Obama Administration and Congress try to address a high unemployment rate. The focus of a potential bill in 2010 is on green jobs, in particular, three major efficiency provisions are in development – residential retrofits, industrial and CHPefficiency grants, and commercial retrofits. As of this writing, prospects for the first two provisions are promising; the third was developed later and its prospects are unclear. Some additional money may also go toward renovation of public housing, including efficiency improvements and to replacement of inefficient manufactured homes.

Fact Sheet: Energy Efficiency—Jobs and Investment

Fact Sheet: People Who Save Energy: Efficiency Workers

To learn more or contact a researcher, visit our National Policy Local Policy, State Policy, or Economics and Finance Program